How a Physics Whiz Made a Fortune Betting on Nature’s Catastrophes

John Seo used his scientific knowledge to develop a winning formula for trading catastrophe bonds — a market that’s booming thanks to climate change and inflation.

When thousands of homeowners in Florida and Louisiana purchased their hurricane insurance, they probably had no idea that John Seo stood to make a big profit if their properties got through the next three years unscathed.

Unbeknownst to them, Seo, a 57-year-old hedge fund manager in southern Connecticut, is the reason why millions of people from New Zealand to Chile have financial protection against natural disasters. His fund, Fermat Capital Management, owns the world’s biggest collection of catastrophe bonds — complex financial instruments that insurers issue to cover risks they can’t handle.

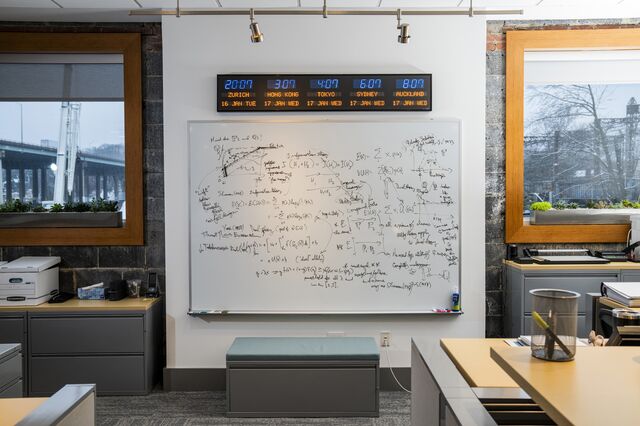

Fermat is an oddity in the hedge fund world. Its modest office, in the affluent town of Westport, sits in a former post office across from an auto-repair shop. There are meteorology journals in the reception area and equations scrawled on a whiteboard. Investment decisions are guided by complicated weather-risk computer models powered by large servers that whirr ceaselessly behind a glass window.

Seo has been trading cat bonds since their infancy, and for two decades Fermat has quietly operated in a niche corner of the financial market. Last year was different. Insurers, worried about more destructive storms, wildfires and floods, issued a record $16 billion of cat bonds. That brought the market’s total size to $45 billion, according to Artemis, which tracks unusual insurance strategies. Meanwhile, buyers demanded more interest because inflation made rebuilding more expensive.

Investing in cat bonds was the most profitable hedge fund strategy of 2023. Fermat delivered a 20% return, beating the average 8% achieved by hedge funds as a whole. While other cat bond funds did well too, Fermat's $10 billion portfolio — capturing a quarter of the market — made it by far the most prolific investor to take advantage of a bumper year.

Cat bonds investors are gambling on nature. If a disaster they’ve bet on occurs, their money is used to settle insurance claims. If it doesn’t, they get handsome returns. For decades, the instruments were a last resort reserved for super-rare events, such as a cataclysmic storm on the scale of Hurricane Katrina. But multibillion-dollar calamities have become alarmingly frequent on a warmer planet.

“The insurance market is on edge,” says Seo. “It’s freaked out about risk and wants as little as possible.”

Many insurers are already charging more to protect customers from devastating weather. In places like Florida and California, where people continue to buy expensive homes along vulnerable coasts and near wildfire-prone areas, some providers have pulled out entirely. Less than a third of last year’s $380 billion in global climate losses was covered by insurance, according to broker Aon Plc.

Millions of people in poorer countries don’t have any safety net if a climate tragedy occurs. The World Bank, which issues cat bonds to help developing nations, hopes to increase its outstanding debt to $5 billion over the next five years from $1 billion today.

“You’ll see us doing cat bonds beyond hurricanes, pandemics and earthquakes,” says Michael Bennett, who heads a World Bank team that issues cat bonds and other derivatives. That could potentially include droughts and floods. “We’re very ambitious.”

In December, Seo and his team gathered to discuss the cat bond covering homes in Florida and Louisiana. It was an unseasonably warm 64 degrees in Westport as Earth’s hottest-ever year drew to a close.

The traders weighed the possibility of a named storm hitting the area in the next three years. The offer document suggested there was only a 1.6% chance that would happen, but Fermat’s model indicated a more worrisome 2.16%. Ultimately they bought just $15 million of the securities — a fifth of the total offering. Fermat received a risk premium of 13.5%, one percent higher than the insurer had hoped to pay.

Seo, who has a PhD in biophysics from Harvard University, founded Fermat in 2001 with his brother Nelson, an economics graduate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In a room above Seo’s garage, the two built a science-based model to weigh the probability of a natural disaster against the returns of a cat bond. They named the fund after Pierre de Fermat, a French mathematician who helped lay the foundation for probability theory.

One of Fermat’s strategies, for example, is inspired by the laws of physics that govern how airplanes fly.

Imagine two graphs. One plots the probability of an event against potential losses, the other shows how much profit Fermat could make at different levels of risk. When the two curves are overlaid, they resemble the cross-section of a plane wing: bulbous at the front and gradually tapering to a thin tip, like a tadpole.

The shape, known as an airfoil, makes modern inventions from helicopter blades to yacht sails more aerodynamic. In Fermat’s case, the airfoil’s lift is the expected return on a cat bond, the turbulence it faces is market volatility, and its speed reflects market conditions. The firm now has a team of 35 quants, traders and programmers working off the Seos’ original code, ingesting newer and better weather models to achieve maximum lift and minimum turbulence.

“We’re constantly having to adjust the shape of the airfoil as new cat bonds come into the market, and as new uncertainties like wildfires show up,” says Seo. “So far, we’ve experienced persistent lift and had only a few, sudden losses of altitude.”

One of those times was 2005, when seven major hurricanes — including Katrina — hit the US. Fermat’s portfolio fell 3% while the hedge fund industry notched an average 9% gain. There were similar losses after Hurricane Ian struck in 2022. Part of the reason cat bonds did so well last year was a mild US hurricane season, which meant fewer investor payouts.

Fermat uses another scientific trick to process large amounts of data, allowing it to do things like quickly assess hurricane risk for millions of homes along a crowded coast. A traditional catastrophe-risk model uses brute force, the equivalent of sticking a multitude of color-coded pins into a map, then adding more and more pins to reflect population movements. The clutter makes it hard for an investor to see the risk.

Astrophysicists face a similar problem. To track the evolution of the universe for even a millisecond, they must pinpoint billions of individual stars then use paired-gravity calculations to compute all the forces at play. It would take years.

A method called clustering simplifies the job. Fermat uses it to boil down the details of, for instance, two million relatively similar homes into a single giant home. Measuring a hurricane’s impact is now a lot easier. It’s an approximation, but it makes calculations much faster.

Fermat also moves quickly when a disaster looms. Say there’s a hurricane headed toward Florida. Nervous investors might offload their cat bonds at a cheaper price. If Fermat’s traders believe the storm will weaken, change direction or simply cause lower-than-expected insured losses, they could snap up the securities for a tidy profit.

Being able to make those rapid decisions is why Zurich-based Gam Investments, Seo’s largest client, trusts him to manage $5 billion. “The team have demonstrated their expertise by actively trading billions of dollars in catastrophe bonds through a series of large insurance industry events and natural catastrophes,” says Ralph Gasser, who leads Gam’s fixed-income investment specialists.

The price to keep people safe from natural catastrophes has been rising for some time. Reinsurers, which backstop the insurance industry, aren’t built to withstand tens of billions in damages from a single event.

Richard Sandor was one of the first people who saw Wall Street as the answer. In 1973, the former Chicago Board of Trade chief economist proposed creating a tradable financial product to cover mounting insurance losses. After Hurricane Hugo hit the US in 1989, leaving insurers with a bill of more than $4 billion, Sandor began devising the derivatives that would eventually morph into cat bonds.

Hurricane Andrew slammed into southern Florida three years later. The storm caused about $15 billion in insured damages. A Boston researcher named Karen Clark was the only one who saw the astronomical figure coming. Her models, which layered predictive storm data against property exposure, introduced a new way to look at climate risk.

Until then, insurers judged risk by looking backward. If the company had never suffered high payouts in an area before, it was seen as low risk. They hadn’t baked in rapidly rising property prices and the likelihood that there were storms ahead unlike any they’d seen before.

Today, Clark runs a company that sells risk and weather models to many cat bond investors. Her team estimates that insured hurricane losses are 11% higher than they would have been without global warming.

Sandor, now 82, says allowing private investors to mop up climate risk is more important than ever. “Back then a hurricane went through potato fields in the Hamptons,” Sandor says. “Now it rips through $10 million houses.”

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. took the lead in establishing the cat bond market and since 2006 has overseen at least $14 billion in weather-related transactions. Michael Millette headed the team that structured the deals. He recalls the skeptical reactions he received when marketing one of the first big offerings in 1997, a $480 million bond to cover US hurricanes. Asset managers “couldn’t understand or price the deal,” he says.

Seo, meanwhile, was at Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. doing just that. One of his earliest finance jobs involved concocting exotic derivatives to cover seemingly random events. One protected a company against a systemic computer crash. Another covered the prize money if someone hit a hole-in-one at a charity’s golf tournament.

“Whatever it was, we would put a price on it and sell it,” Seo says.

Last year’s record cat bond profits have started to draw in more mainstream finance firms and even retail investors.

Still, the securities can only do so much in an increasingly dangerous world. Most are issued for rare events, such as a once-in-a-century typhoon. They have a poor track record with so-called secondary perils — thunderstorms, wildfires and floods that are more costly than before.

Seasoned cat bond investors, such as Twelve Capital, Tenax Capital and Elementum Advisors, are wary of secondary perils because they’re less extreme but more frequent. That makes it harder to predict when they’ll strike and how much damage they’ll do. Many particularly dislike flood risk because it’s notoriously difficult to quantify.

Clark says she now spends a lot of her time analyzing secondary perils. “The potential for $10 billion and $20 billion convective storms and wildfires” is increasing, she says. “That’s where the cat bond market can grow.”

Seo’s obsession with cat bonds started as a tantalizing math challenge — and a chance to prove his father wrong.

When he was 10, Seo and his father, an economist, had a spirited, all-night discussion about the “investor’s choice” conundrum. It pits two investments with the same expected returns and volatility, but different probability distributions, against each other.

The first is the familiar, smooth bell curve. The second looks like the top half of the Batman logo, bumpy and disorderly. The bell curve captures everyday occurrences and is well understood. The Batman curve, depicting rare events, drives statisticians crazy because the risks are much harder to compute.

The elder Seo said the problem couldn’t be solved. It was like asking a buyer to choose between two cars with identical price and performance. Mathematically speaking, there was no way to say if one investment would be more profitable than the other.

But Seo intuitively felt that the bumpy curve was the better option. The bell curve was predictable but “sterile,” he says, while the Batman logo presented more opportunities to win. Years later, he would find that very dynamic at the heart of cat bonds — a world of extreme profits and losses.

More than three decades after encountering that childhood puzzle, Seo wrote a mathematical proof that showed the “investor’s choice” was solvable. His father scrutinized the paper for two weeks before delivering a verdict.

“You did it,” he said.